Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Gulf of Honduras

A Programme of the Governments of the Gulf of Honduras Countries, with the assistance

of the Inter-American Development Bank

Gulf of Honduras

Preliminary Transboundary

Diagnostic Analysis

Final Draft

August, 2003

Global Environment Facility--Inter-American Development Bank

Project Development Facility (PDF-B)

i

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Table of Contents

1.0 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 1

1.1 TDA CONTENT AND PROCESS ................................................................................................. 1

1.2 SCOPE OF THE TDA ................................................................................................................. 1

2.0 PHYSICAL AND BIOGEOCHEMICAL SETTING............................................................... 4

2.1 WATERSHED ............................................................................................................................ 4

2.1.1 Drainage Basins............................................................................................................... 5

2.1.2 River Discharge ............................................................................................................... 6

2.1.3 Sediment Discharge from Rivers ..................................................................................... 7

2.1.4 Shoreline Classification ................................................................................................. 15

2.1.5 Climate........................................................................................................................... 15

2.2 GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY......................................................................................... 20

2.2.1 Geology .......................................................................................................................... 20

2.2.2 Coastal Processes and Coastal Erosion ........................................................................ 21

2.3 OCEANOGRAPHY.................................................................................................................... 21

2.3.1 Seawater Properties in the Gulf of Honduras................................................................ 25

2.3.2 Ocean and Coastal Currents ......................................................................................... 31

2.4 ECOSYSTEMS VULNERABLE TO WATER QUALITY DEGRADATION IN THE GULF OF

HONDURAS...................................................................................................................................... 33

2.4.1 Mangroves/Coastal Forests........................................................................................... 33

2.4.2 Seagrass Meadows......................................................................................................... 34

2.4.3 Coral Reefs..................................................................................................................... 34

2.5 BIODIVERSITY AND PROTECTION STATUS IN THE GULF OF HONDURAS AND ITS

WATERSHED .................................................................................................................................... 35

2.5.1 Marine Biodiversity........................................................................................................ 35

2.5.2 Endangered Species ....................................................................................................... 36

2.5.3 Protected Areas.............................................................................................................. 38

3.0 SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND DEVELOPMENT SETTING.................................................... 42

3.1 POPULATION AND DEMOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN THE GULF OF HONDURAS WATERSHED ....... 42

3.1.1 Current Population and Population Growth Rates ....................................................... 43

3.1.2 Literacy Rates ................................................................................................................ 44

3.1.3 Access to Healthcare...................................................................................................... 44

3.2 REGIONAL ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................................. 45

3.2.1 Structure of Economic Output in the Watershed ........................................................... 45

3.2.2 Future Trends in Economic Output in the Watershed for the Next 10 Years ................ 46

3.3 INDUSTRIES IMPACTING AND IMPACTED BY THE GULF OF HONDURAS .................................. 47

3.3.1 Agriculture ..................................................................................................................... 47

3.3.2 Commercial and Artisanal Fisheries ............................................................................. 47

3.3.3 Aquaculture.................................................................................................................... 48

3.3.4 Tourism .......................................................................................................................... 49

3.3.5 Marine Transport ........................................................................................................... 50

June 2, 2003

i

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

3.3.6 Industry .......................................................................................................................... 51

4.0 OVERVIEW OF APPLICABLE INSTITUTIONAL AND REGULATORY

FRAMEWORKS .............................................................................................................................. 53

4.2 MARITIME ADMINISTRATION................................................................................................. 55

4.2.1 Belize .............................................................................................................................. 55

4.2.2 Guatemala...................................................................................................................... 57

4.2.3 Honduras........................................................................................................................ 59

4.3 OTHER PROJECT-RELATED PROGRAM AREAS........................................................................ 61

5.0 MAJOR PERCEIVED PROBLEMS AND ISSUES ............................................................. 67

5.1 NEGATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS ARISING FROM EXISTING AND FUTURE PORT

OPERATIONS AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT: ..................................................................... 70

5.1.1. Port Expansion and Maintenance Activities.................................................................. 75

5.1.2 Loading/Offloading and Storage of Cargo .................................................................... 78

5.1.3 Waste Generation and Handling ................................................................................... 79

5.1.4 Ballast Water.................................................................................................................. 80

5.1.5. Port-Related Industry..................................................................................................... 81

5.2 NEGATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS ARISING FROM MARINE ACTIVITIES.......................... 83

5.2.1 Degradation Resulting from Oil and Chemical Discharge ........................................... 83

5.2.2 Degradation Resulting from Other Marine Activities ................................................... 92

5.2.3 Sensitive Area Mapping ................................................................................................. 92

5.3 OTHER LAND-BASED ACTIVITIES (OTHER THAN SHIPPING-RELATED) CAUSING

DEGRADATION OF THE ECOSYSTEMS OF THE GULF OF HONDURAS................................................... 96

5.3.2 Logging .......................................................................................................................... 98

5.3.3 Municipal Sewage Discharge ...................................................................................... 100

5.3.4 Aquaculture.................................................................................................................. 100

5.3.5 Tourism ........................................................................................................................ 101

5.3.6 Industrial Discharge .................................................................................................... 102

5.4 PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE RELATIVE IMPORTANCE AND LOCAL AND

TRANSBOUNDARY IMPACT OF LAND-BASED VS. SHIP-BASED SOURCES OF POLLUTION ............... 110

6.0 STAKEHOLDER ANALYS IS .............................................................................................. 115

6.1 LINKS WITH OTHER INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONALLY SIGNIFICANT PROJECTS AND

INSTITUTIONS ................................................................................................................................ 115

6.2 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATIONS ......................................................................................... 118

6.2.1 Public Sector National and Local Government ........................................................ 119

6.2.2 Civil Society ................................................................................................................. 122

6.2.3 Private Sector............................................................................................................... 123

7.0 ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY OBJECTIVES ................................................................ 125

8.0 BIBLIOGRAPHY................................................................................................................... 127

June 2, 2003

ii

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

List of Abbreviations

APPENDIX B

Causal Chain Analysis

APPENDIX C

Supplementary Data

APPENDIX D

Supplementary Figures (Maps)

(separate file)

List of Figures

Figure 2.0-1. Gulf of Honduras Project Area............................................................................................................................. 4

Figure 2.0-2. Gulf of Honduras Watershed................................................................................................................................ 4

Figure 2.1-1. Rivers in the Gulf of Honduras Watershed........................................................................................................ 6

Figure 2.1-2. Monthly Average Discharge for the Rio Grande River, Honduras................................................................ 7

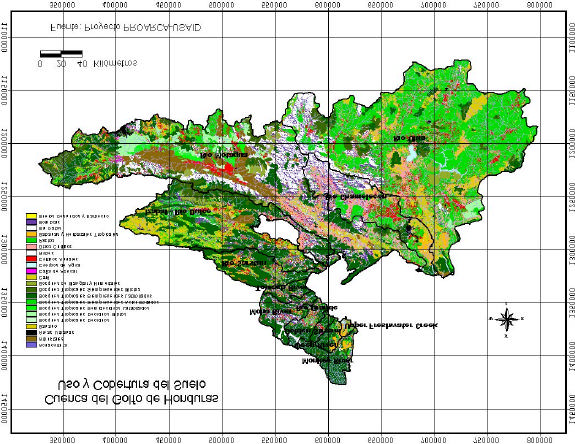

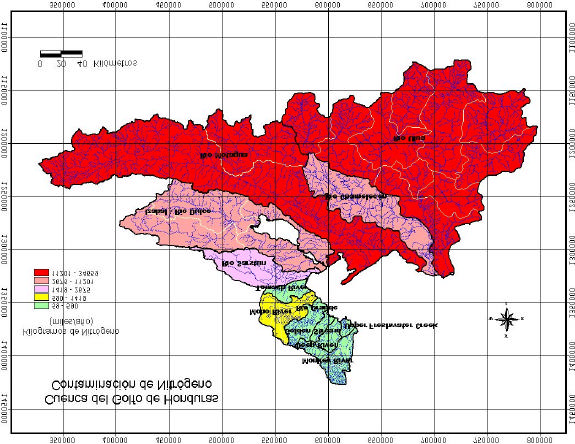

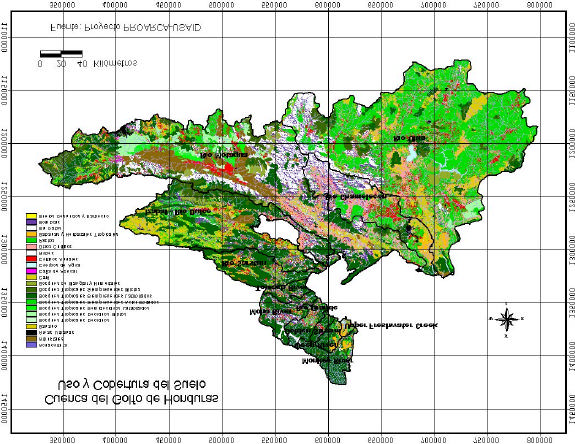

Figure 2.1-3. Land Use Coverage Gulf of Honduras ............................................................................................................ 10

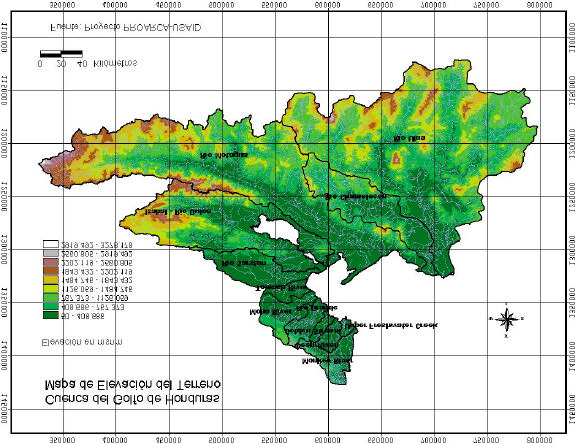

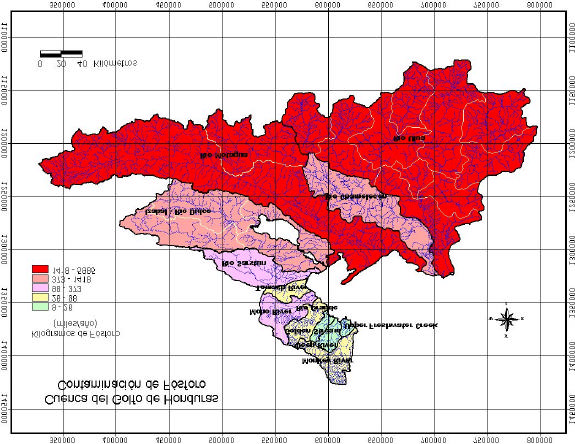

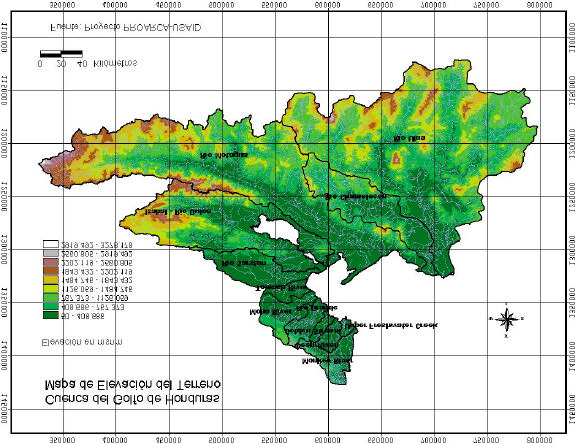

Figure 2.1-4. Digital Elevation Map- Gulf of Honduras ..................................................................................................... 11

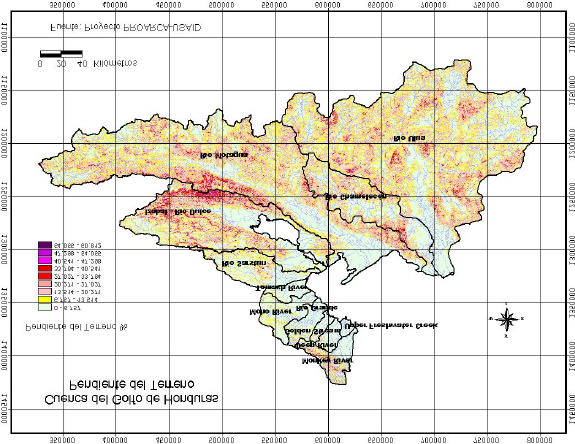

Figure 2.1-5. Slope Map- Gulf of Honduras Watershed........................................................................................................ 12

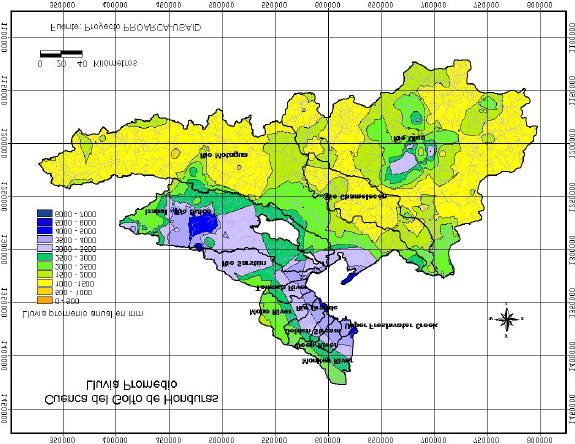

Figure 2.1-6. Average Rainfall- Gulf of Honduras Watershed............................................................................................. 13

Figure 2.1-7. Erosión Potential Index- Gu lf of Honduras Watershed................................................................................ 14

Figure 2.1-8. Mean Monthly Temperatures for the Gulf of Honduras Marine Area ........................................................ 16

Figure 2.1-9. Regional Precipitation Patterns in the Gulf of Honduras .............................................................................. 17

Figure 2.1-10. Mean Monthly Precipitation in the Gulf of Honduras ................................................................................. 18

Figure 2.1-11. Seasonal Evolution of Sea Surface Temperatures (Pathfinder AVHRR) and Surface Winds

(NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis Project) for the Caribbean Sea. ......................................................................................... 19

Figure 2.1-12. Map of Hurricane Tracks in the Gulf of Honduras, 1921-1999................................................................. 20

Figure 2.3-1. The Caribbean Basin: Bathymetry and Circulation........................................................................................ 24

Figure 2.3-2. Surface (left) and Bottom (right) Water Temperature Variations at Cayos Cochinos in 1993 1996. 25

Figure 2.3-3. Surface Salinity Distribution in the Snake Cays (Western Gulf) ................................................................. 27

Figure 2.3-4. Schematic Representation of Salinity Distribution and Flows in a Typical Estuarine System............... 28

Figure 2.3-5. AQUA MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) image of the Gulf of Honduras

Area (MODIS Band Combination: 1, 4, 3) Showing a Pattern of Low Turbidity Water Formed on the Inner

Side of the Barrier Reef...................................................................................................................................................... 29

Figure 2.3-6. Seawater Transparency Distribution Close to Deep River Mouth in February 1999............................... 30

Figure 2.3-7. Oceanographic Currents in the Gulf of Honduras .......................................................................................... 32

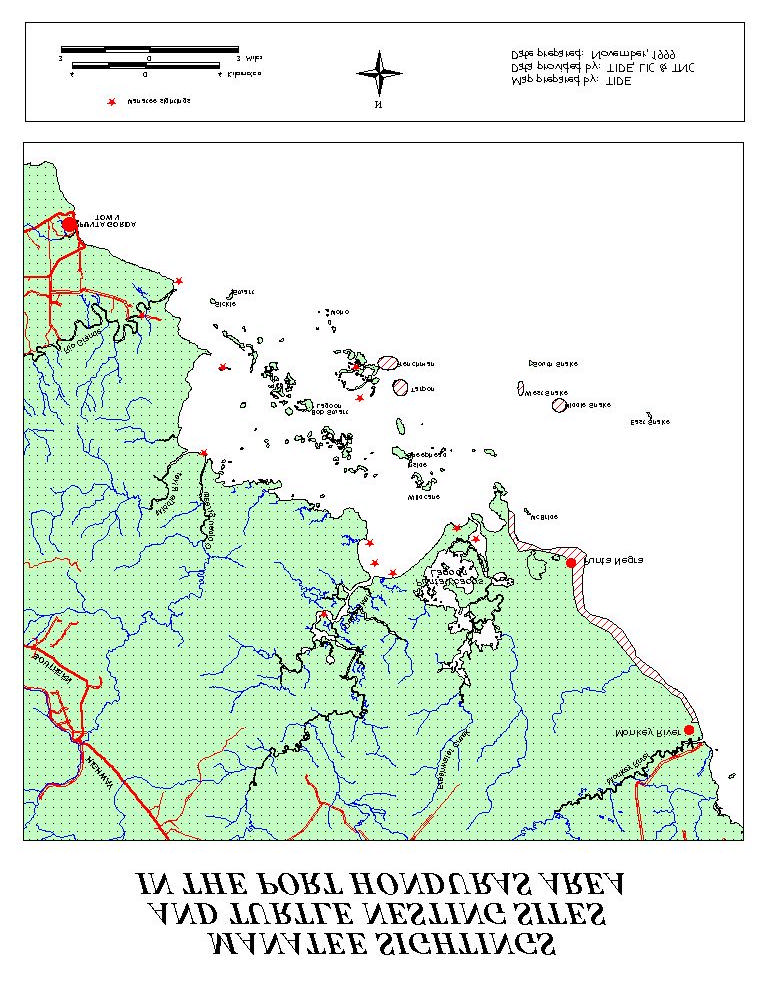

Figure 2.5-1. Manatee Habitats and Turtle Nesting Areas in the Port Honduras Area .................................................... 37

Figure 2.5-2. Protected Areas in the Gulf of Honduras ......................................................................................................... 40

Figure 3.1-1. Population in the Gulf of Honduras Watershed by Administrative District............................................... 43

Figure 3.1-2. Population Density in the Coastal Zone of the Gulf of Honduras Watershed........................................... 43

Table 4.1-1. Figure Relevant International Conventions Related to Maritime Administration...................................... 54

Figure 4.2-2. Maritime Organization in Guatemala ................................................................................................................ 59

Figure 4.2-3. Organization of the National Port Authority in Honduras (next page)....................................................... 59

Figure 4.3-1. Belize Government Structure for Environmental Protection........................................................................ 62

Figure 4.3-2. Guatemala Government Structure for Environmental Protection................................................................ 64

Figure 4.3-3. Honduras Government Structure for Environmental Protection.................................................................. 66

Figure 5.1-1. Ecosystems of the Gulf of Honduras and its Watershed................................................................................ 68

Figure 5.1-1. Belize City Port ..................................................................................................................................................... 70

Figure 5.1-2. Port of Big Creek.................................................................................................................................................. 71

June 2, 2003

iii

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 5.1-3. Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla ......................................................................................................................... 72

Figure 5.1-4. Puerto Barrios........................................................................................................................................................ 73

Figure 5.1-5. Puerto Cortés ......................................................................................................................................................... 74

Figure 5.2-1. Sensitive Areas in the Gulf of Honduras Particularly Vulnerable to Contamination from Oil and

Chemical Spills .................................................................................................................................................................... 93

Figure 5.2-2. Sensitive Vulnerable Areas Adjacent to the Port of Big Creek.................................................................... 94

Figure 5.2-3. Sensitive Vulnerable Areas Adjacent to Puerto Santo Tomás de Castilla and Puerto Barrios ............... 94

Figure 5.2-4. Sensitive Vulnerable Areas Adjacent to Puerto Cortés.................................................................................. 95

Figure 5.3-1 Land Use in the Gulf of Honduras...................................................................................................................... 96

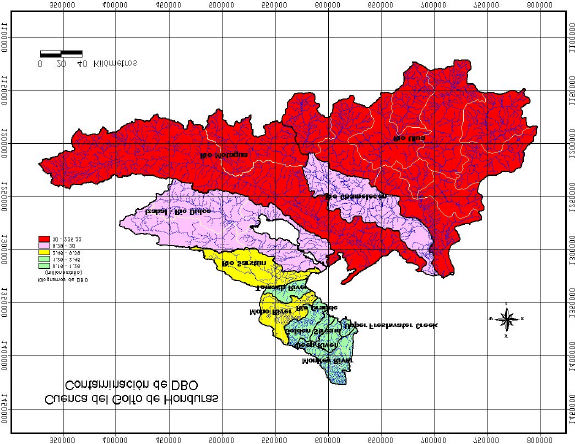

Figure 5.3-2. Potential BOD Loads- Gulf of Honduras Watershed...................................................................................107

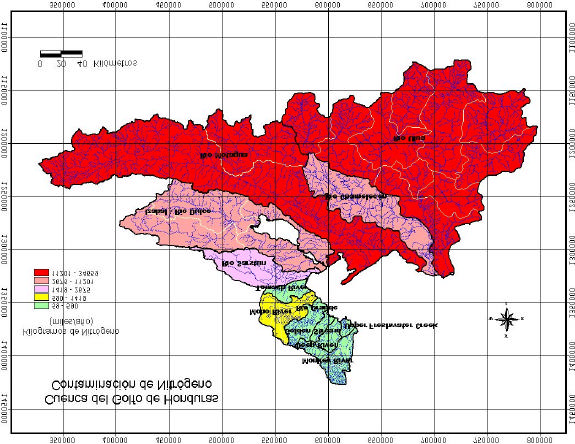

Figure 5.3-3. Potential Nitrogen Loads- Gulf of Honduras Watershed.............................................................................108

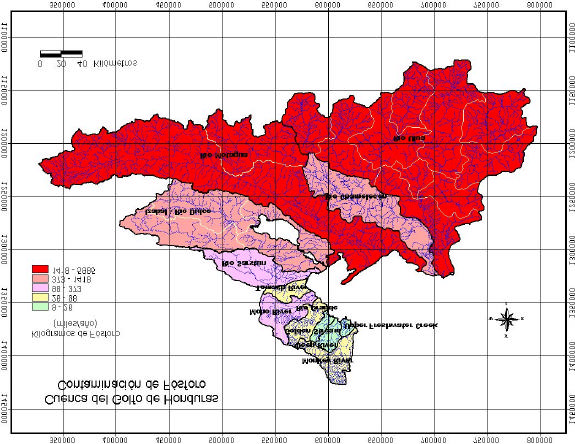

Figure 5.3-4. Potential Phosphorus Loads- Gulf of Honduras Watershed........................................................................109

List of Tables

Table 2.1-1. Major Watersheds of the Gulf of Honduras ........................................................................................................ 5

Table 2.1-2. Subsidiary Watersheds of Belize ........................................................................................................................... 5

Table 2.1-3. Major Rivers Entering the Gulf of Honduras...................................................................................................... 6

Table 2.1-4. Preliminary Estimation of the sediment Loasd of the main tributaries of the Gulf of Honduras............... 9

Table 2.4-1. Mangrove Coverage and Protection in the Gulf of Honduras Waters hed in Guatemala, 1999................ 34

Table 2.5-1. Summary of Biological Diversity in Caribbean Coastal and Marine Areas in Belize, 1998 .................... 36

Table 2.5-2. Invertebrates and Urochordates in the Honduran Coastal Waters of the Caribbean.................................. 36

Table 2.5-3. Status of Coastal and Marine Species of Primary Interest in Belize, 1998.................................................. 38

Table 2.5-4. Status of Coastal & Marine Species of Primary Interest in Guatemala ........................................................ 38

Table 2.5-5. Protected Areas in the Gulf of Honduras Region ............................................................................................. 40

Table 2.5-6. Areas for Existing Marine Protected Areas in Belize ...................................................................................... 41

Table 3.1-1. Human Development Indicators.......................................................................................................................... 42

Table 3.1-2. National Population and Population Growth Rates in the Gulf of Honduras Countries............................ 43

Table 3.1-3. Population Density in the Southern Region of Belize by District, 1970-1998............................................ 43

Table 3.1-5. Literacy rates and education spending in the Gulf of Honduras countries .................................................. 44

Table 3.1-5. Healthcare Statistics in the Gulf of Honduras Countries ................................................................................ 45

Table 3.3-1. Status of Active Shrimp Farms in the Southern Region of Belize, 1999..................................................... 49

Table 3.3-2. Cargo Imported/Exported Through Ports Annually (Metric Tons)............................................................... 51

Table 3.3-3. Port Ship Calls in the Gulf of Honduras ............................................................................................................ 51

Figure 4.2-1. Maritime Administration for Belize (next page)............................................................................................. 55

Table 5.1-1. Port Equipment....................................................................................................................................................... 75

Table 5.2-1. Hydrographic Component Gap Analysis Summary Findings..................................................................... 85

Table 5.2-2. Hydrographic Component Gap Analysis -- Belize ........................................................................................... 86

Table 5.2-3. Hydrographic Component Gap Analysis -- Guatemala ................................................................................... 87

Table 5.2-4. Hydrographic Component Gap Analysis -- Honduras..................................................................................... 88

Table 5.2-5. Hydrographic Surveys and Data Availability in the Region .......................................................................... 89

Table 5.3-1. Estimate of Nitrate and Phosphate Loads into Surface Waters by Banana and Citrus Production in the

District of Stann Creek, Belize1994................................................................................................................................. 97

Table 5.3-2. Agricultural Wastes and Inputs to the Environment........................................................................................ 98

Table 5.3-3. Logging Activity .................................................................................................................................................... 99

Table 5.3-4. Sanitation Coverage by District in Southern Belize, 1994 ...........................................................................100

Table 5.3-5. Parameters Monitored by the Shrimp Mariculture Industry in Southern Belize, 1998............................101

Table 5.3-6. Major Industries (Excluding Those Associated with Ports).........................................................................103

Table 5.3-7. BOD, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Potential Loads to the Gulf of Honduras................................................105

Table 5.4-1. Ranking Scheme for Relative Assessment of Impacts ..................................................................................111

Table 5.4-2. Relative Ranking of Environmental Importance of Various Land-Based and Ship-Based Activities ..113

June 2, 2003

iv

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

1.0 Introduction

1.1

TDA Content and Process

According to GEF guidance, the purpose of conducting a Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) is to

scale the relative importance of sources and causes, both immediate and root, of transboundary `waters'

problems, and to identify potential preventive and remedial actions. The TDA provides the basis for

development of both the National Action Plans (NAPs) and the Strategic Action Programme (SAP) in the

area of international waters of the GEF.

This TDA, therefore, summarizes information available from the region, gathered both as part of ongoing

national activities within the littoral states, as well as information made available from a variety of

internationally supported activities in the region.

The methodology for a TDA consists of the following steps, at a minimum:

·

Identification of major perceived problems and issues, including status and gaps

·

Classification as national or transboundary in nature

·

Causal chain analysis (including root causes)

Because the list of possible interventions and actions arising from the analysis of the Gulf of Honduras

problems is so large, a mechanism was needed in order to prioritize the interventions. Borrowing from

methodology commonly used in the European Union and other regions, the present preliminary TDA

identifies a series of draft Environmental Quality Objectives (EQOs), which represent the regional

perspective of major goals for the regional environment. The use of EQOs helps to refine the TDA

process by achieving consensus on the desired status of the Gulf of Honduras. Within each EQO (which

is a broad policy-oriented statement), several draft specific targets were identified. Each target generally

had a timeline associated with it, as well as a specific level of improvement or target status. Thus, the

targets illustrate the chain of logic for eventual achievement of the EQO. Specific interventions or actions

were identified in the Project Brief to permit realization of each of the targets within the designated time

frame.

A prime purpose of the TDA is to determine priority Transboundary problems. EQOs and the entire TDA

process may also specify more national problems or issues. Although these national issues are included

in the TDA, they are identified as not having strong transboundary implications, and therefore will be of

lesser concern to the GEF process.

In summary, this TDA follows the GEF TDA Guidelines for International Waters projects. An additional

step was achieved, however, that is, the use of EQOs to facilitate consensus on the desired state of the

Gulf of Honduras after the next pentade or decade. The EQOs naturally led to the identification of

specific targets to be met within the desired time frame, which then led to the identification of specific

interventions and actions that can be considered in the framework of the SAP. GEF interest will focus on

those priority transboundary problems and issues.

1.2

Scope of the TDA

This TDA is being developed in support of the project for the environmental management of the Gulf of

Honduras, "Environmental Protection and Maritime Transport Pollution Control in the Gulf of

June 2, 2003

1

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Honduras," which has a primary focus on some of the major environmental problems and issues of the

Gulf leading to the degradation of marine and coastal ecosystems by human activities. The present

analysis covers the three countries that are located in the Gulf of Honduras: Belize, Guatemala and

Honduras. The analysis focuses on prioritizing environmental stressors on the Gulf's coastal and marine

ecosystems that are derived from pollution related to the maritime shipping industry in the region and

land-based sources of pollution in the watershed.

This study is meant to complement the Threat and Root Cause Analysis developed by the World

Bank/GEF/CCAD Project for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef

System (MBRS) which identified the tri-national area of the Gulf of Honduras as a critical area. In

particular, port and ship-based pollution were recognized as significant threats to the health of the reef

ecosystem and are consequently to be addressed by this complementary project. This project also

complements the on-going UNDP/GEF Project for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of the Barrier

Reef Complex in Belize.

Many institutions and experts from the Gulf of Honduras region participated in the development of this

preliminary TDA. After the initial determination of stakeholders and interested parties was made, a

public consultation process was developed to inform and incorporate the input from representative

members of each of the target groups in the study area. Public consultations were conducted through a

combination of regional workshops held in each of the three countries and individual meetings. One

international stakeholders meeting was held on November 21, 2002 in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. A

second meeting was held on March 20-21, 2003 in Guatemala City, Guatemala and a third stakeholder

meeting is to be held on June 12-13, 2003 in Belize City, Belize.

The regional stakeholder advisory committee has had an important role in reviewing and providing

comments on the development of this preliminary TDA. The stakeholder committee consists of

approximately twenty-five members from representative national line agencies and municipal

governments, merchant marines and naval authorities, port authorities, nongovernmental organizations,

and industry from Guatemala, Honduras and Belize. Participation has been balanced to maintain a

representative group of stakeholders from the three countries. The stakeholder committee has provided

background data for this analysis, reviewed drafts of this document and provided information concerning

perceptions of problems and challenges facing regulatory agencies, the regulated community and civil

society organizations in the region.

While much data were obtained through this process, only partial information on the environmental status

was provided by each country, so this TDA is a summary of available information only. Where possible,

additional sources of data were sought.

The major sources of information are listed in the bibliography accompanying this TDA. Gaps in

information available for this Preliminary TDA can be filled during the full GEF project when the TDA

will be updated and completed.

Based on the early project development activities, as well as the regional consensusbuilding process, this

Preliminary TDA identifies a single major perceived problem and issue for the Gulf of Honduras:

Degradation of Coastal and Marine Ecosystems

The following causes of the MPPI have been determined and are examined in detail in the following

sections:

June 2, 2003

2

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

·

Negative environmental effects arising from existing and future port operations and infrastructure

development

·

Negative environmental effects arising from marine activities

·

Other Land-Based Activities (other than shipping-related) causing degradation of the ecosystems of

the Gulf of Honduras

Below, each of these problems and issues is addressed from a status perspective. It answers the

questions: What do we know about this problem/issue? What data support the quantification of the

extent of the problem/issue? Do the data support these as real problems and issues, or just as perceptions?

This analysis took place on a scientific level, including biological, hydrological, physical, social, and

other perspectives on the problem. This is in effect the "status" assessment.

The next step was to perform the causal chain analysis; the major perceived problems and issues were

analyzed to determine the primary, secondary, and root causes for these problems/issues. Identification of

root causes is important because root causes tend to be more systemic and fundamental contributors to

environmental degradation. Interventions and actions directed at the root causes tend to be more

sustainable and effective than interventions directed at primary or secondary causes. Because the

linkages between root causes and solutions of the perceived problems are often not clear to policymakers,

however, interventions commonly are mistakenly directed at primary or secondary causes. This

Preliminary TDA attempts to clarify the linkages between root causes and the major perceived problem to

encourage interventions at this more sustainable level.

This Preliminary TDA faced several challenges in its preparation, including a lack of comple te

information and data, and a short time frame for its preparation.

June 2, 2003

3

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

2.0 Physical and Biogeochemical Setting

The Gulf of Honduras, bounded by Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras, covers an area of approximately

10,000 square kilometers (Figure 2.0-1). The Project Area for the proposed GEF project extends from

Punta Sal, Punta Isopo, in the southeast, northwest towards Sittee Point along the Belize shoreline,

inwards along the northern border of the Maya Mountains watershed, southwestward along the various

watersheds of Belize (numerous watersheds, lumped here as the Maya Mountain watersheds), Guatemala

(Sarstoon, Laguna Izabal, Motagua), and Honduras (Ulua, Lean, Cuyamel, Chamelecon), reaching the

coast once again at Punta Isopo (Figure 2.0-2).

Figure 2.0-1. Gulf of Honduras Project Area

(See Appendix D)

Figure 2.0-2. Gulf of Honduras Watershed

(See Appendix D)

The Gulf of Honduras abuts the southwestern Caribbean Sea, having water depths of up to 2000 m. Its

western portion is lined by the MesoAmerican Barrier Reef Complex, stretching along the waters of

Belize into Guatemala. Inside the barrier reefs are shallow inner reef complexes, with many cays and

shoals. Along the Guatemala region, the Gulf of Honduras includes the Bahía de Amatique, and the

smaller bays of Graciosa and Santo Tomás de Castilla. Along the Honduras coast, the Gulf of Honduras

includes the Bahia de Cortés adjacent to Puerto Cortés.

The Gulf of Honduras is influenced strongly by both open ocean (Caribbean Sea) dynamics, as well as

reef-controlled dynamics, river inflow, sediment fluxes, and hurricane passage. Although located in a

region having reasonably stable annual climate, a seasonal wet-season, dry season combines with ocean

variability to impose scales of variability on the ecosystem. The complex interaction of open ocean

waters, coastal multiple time ocean processes, and riverine flows is reflected in geographically-varying

ecosystem components that contribute to the region's valuable ecological diversity.

Major coastal and marine ecosystem types along this region include river mouths with their estuaries,

coastal lagoons, coastal embayments, inner cayes, mid-lagoon cayes, barrier reefs and the open ocean

(Heyman and Kjerfve, 2000). Important coastal and marine resources include mangrove wetlands,

seagrass beds, barrier reefs, shrimp, marine turtles (green, hawksbill, leatherback, and loggerhead) and

manatees. Marine protected areas dot the coast, and include some dozen or more coastal and marine

reserves and parks.

Approximately half a million people live along the coast of the Gulf of Honduras, whereas some 12.4

million people live in the adjacent watersheds. Major coastal population centers include Puerto Barrios

and Livingston in Guatemala, San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortés in Honduras, and Punta Gorda and

Belize City in Belize. Shipping, bananas, fisheries (both subsistence and export), and tourism are major

industries of the region.

2.1

Watershed

The watersheds of the Gulf of Honduras make up some 53,700 km2, distributed with about 5,800 km2 in

Belize, 18,300 km2 in Guatemala, and 29,600 km2 in Honduras.

June 2, 2003

4

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

2.1.1

Drainage Basins

The Project Area within the Gulf of Honduras region is influenced by eight primary watersheds (Figure

2.0-2), whose total area is about 53,700 km2 (Table 2.1-1). There are eighteen subsidiary watersheds in

Belize (Table 2.1-2), three primary watersheds in Guatemala, and four primary watersheds in Honduras,

within the project area. Numerous rivers drain each watershed, but the main rivers are the Sarstoon, Rio

Dulce, Motagua, Chamelecon and Ulua.

Table 2.1-1. Major Watersheds of the Gulf of Honduras

Watershed Name

Countries

Watershed Area (km2)

Major Rivers

Maya Mountains*

Belize

5,800

Sittee River, Swasey

Branch, Rio Grande, Moho

River

Sarstoon

Guatemala, Belize

2,218

Sarstoon River

Rio Dulce -- Laguna Guatemala

3,435

Rio Dulce

Izabal

Motagua

Guatemala,

12,670 (2,141 of which

Motagua River, San

Honduras

are in Honduras)

Francisco River, Piteros

River, Canal de los

Ingleses

Chamelecon

Honduras

4,350

Chamelecon River

Cuyamel

Honduras

2,141

Motagua

Ulua

Honduras

21,230

Ulua River

Lean I

Honduras

3,045

Lean River

Table 2.1-2. Subsidiary Watersheds of Belize

Watershed Name

Watershed Area (km2)

Major Rivers

Freshwater Creek

225

Freshwater, Black Ridge, and

Silk Grass creeks

Sittee River

457

Sittee River and Cocoa, Pull

Shoes, and Blackwater branches

Cabbage Haul Creek

104

Cabbage Haul Creek

South Stann Creek

261

Sittee, Cockscomb, Mexican and

Juan branches of South Stann

Creek

Santa Maria Creek

151

Santa Maria and Silver creeks

Mango Creek

250

Mango Creek

Big Creek

59

Big Creek

Sennis River

76

Sennis River

Pine Ridge Creek

40

Pine Ridge Creek

Monkey River

1,290

Monkey River

Freshwater Creek

138

Freshwater and Payne's creeks

Deep River

352

Big Dry Creek, Machaca Creek,

Warrie Creek, and Deep River

Channel

Golden Stream

206

Golden Stream

Middle River

51

Middle River and Seven Hills

Creek

Rio Grande

727

Rio Grande and Columbia Branch

Moho River

822 (1,189 total)**

Moho River

Temash River

364 (475 total)**

Temash River system

Sarstoon River*

194 (2,218 total)**

Sarstoon River

June 2, 2003

5

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

*Shared by Guatemala and Belize

** unbracketed: drainage area in Belize; in parentheses --- total drainage basin area

2.1.2

River Discharge

Few discharge measurements have been made in the Caribbean watersheds of the Gulf of Honduras, and

those that do exist are generally of short duration, some installed following Hurricane Mitch in 1998 in

order to assist flood disaster planning and prevention. The major rivers are shown in Figure 2.1-1 and

characteristics listed in Table 2.1-3.

Figure 2.1-1. Rivers in the Gulf of Honduras Watershed

(See Appendix D)

Table 2.1-3. Major Rivers Entering the Gulf of Honduras

River Name

Country (ies)

Length (km)

Mean Discharge

(m3/sec)

Sittee River

Belize

32

Stann Creek River

Belize

40

Swasey Branch

Belize

27

Monkey River

Belize

63

Rio Grande

Belize

26

Moho River

Belize

37

Sarstoon

Belize (Black Creek)/

42

160*

Guatemala (San Pedro)

Rio Dulce

Guatemala

42

300*

Motagua

Guatemala

487

530*

San Francisco

Guatemala

Piteros

Guatemala

Ulua

Honduras

358

690* (1,400**)

Chamelecon

Honduras

256

370 * (400**)

* Heyman and Kjerfve, 1999

** Comision Ejecutiva Valle de Sula, 2002

The largest rivers are in Guatemala and Honduras. Due to the proximity of the Belize Maya Mountains to

the coast, the rivers in Belize are more numerous, but smaller in terms of water discharge. The mean

water discharges for the rivers in Belize are 10 to 20 times smaller than those in Guatemala and

Honduras.

Monthly discharge patterns reflect the seasonal rainfall distribution. Figure 2.1-2 shows the seasonal

discharge pattern for the Rio Grande River in Belize. Maximum discharge coincides with the rainy

season (June through October). Lower discharges occur in other months.

June 2, 2003

6

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-2. Monthly Average Discharge for the Rio Grande River, Honduras

Monthly Average Discharge for Rio Grande River

(cubic meters per second)

70

60

50

40

1981-1995

30

20

10

0

January

March April May June JulyAugust

February

October

September November

December

The total mean discharge of rivers to the Gulf of Honduras listed in Table 2.1-3 is about 2,200 m3/sec.

Heyman and Kjerfve estimate a total discharge to the Gulf of 2,400 m3/sec, equivalent to about 76 km3 a

year. FAO estimates a discharge of 43 km3 per year from the Guatemalan rivers, 16 km3 a year from the

Project Area of Honduras (of about 75 km3 a year produced by all of Honduras into the Caribbean), and

about 15 km3 a year from Belize (a total FAO estimate of 74 km3 per year). All three estimates are

relatively similar, giving added confidence to these estimates.

The primary discharge patterns are reflected in the ecology of the region. The small discharges along the

Belize coast are associated with an extensive barrier reef (the second largest in the world after Australia's

Great Barrier Reef). As the influence of the Guatemalan and Honduran rivers is felt, however, the reefs

are not present as continuous barriers. This situation reflects changes in the hydrography, including

visibility, nutrient input, water clarity, sediment inputs, etc.

2.1.3

Sediment Discharge from Rivers

Few data exist on sediment discharge to the Gulf of Honduras. Belize has two types of drainage: one in

the steeper Maya mountain area to the north of Belize, and a second southern coastal plain having lower

slopes. In general, the rocks of the Maya Mountains in Belize are granitic and metasedimentary in nature,

and therefore may erode more slowly than sedimentary rocks of the south. The steep slopes of the

Belizean drainage to the Caribbean suggest that the sediments will be coarse in grain size, and there will

be less than in the much larger rivers of Guatemala and Honduras. This is not to say that the specific

sediment transported yield of the rivers (volume of sediment per unit area) in Belize is smaller than in the

other two countries. In fact, the specific yield may be greater in Belize than the other countries due to its

steeper slopes. Data do not allow determination of the specific yield for all rivers, which represents a

trade-off between the slope of the river/watershed, and the geological materials being eroded.

Human activities can also affect the sediment yield from these areas. Deforestation, agriculture, sand

mining from rivers and construction of dams and reservoirs, all can affect the sediment yield from rivers.

Dams and mining are occurring in all three countries, so sediment yield to the coast is even more

June 2, 2003

7

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

uncertain. Since coastal stability depends in large part on sediment availability, at least in the Guatemalan

and Honduras regions, more gauging stations may be required for coastal zone management purposes.

Limited data on sediment discharge was collected by WRIScS (2001). They monitored suspended

sediment load in the North Stann Creek and Sittee Rivers, and compared those to South Stann Creek.

They estimated a total specific yield for suspended sediments of 32 to 53 tons per km2 per year for 1999,

about 85 % of which came during the rainy season. The total suspended sediment load estimates range

from 2,000 tons per rainy season (North Stann River) to 14,000 tons per rainy season (Sittee River).

These estimates underestimate the total sediment load, since this study did not measure bedload transport.

As part of this study, the erosion potential and potential sediment load were estimated, by assuming an

average concentration of suspended sediments in the rivers. These estimates have large error bars.

From a transboundary context, the natural and human-accelerated sediment delivery to the Gulf plays a

major role. Regional exchange of sediments from rivers occurs through transboundary currents, and

allows dispersal anywhere in this eco-region.

2.1.3.1 Potential Erosion

In order to have a perspective on the erosion problems of the Gulf of Honduras, an analysis was

performed considering three important factors for the erosion process which are: land cover, slope and

rainfall. Overlays of digitals maps for these factors were used in order to generate a map of potenial

erosion for the watershed. The land use map shown in Figure 2.1-3 was used together with digital

elevation maps provide by the USAID-PROARCA project. The digital layers were overlaid to generate

an index by pixel which aggregation results in the erosion potential map. The erosion index was

determined by multiplying for each pixel the slope with a cover factor, which is a function of the land use.

The cover factor was the C factor of the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE). The minimum values used

for each land use were: forest = 0.001, shrubs = 0.030, low vegetation, bare land = 0.500, intensive crops

= 0.200 y other crops and pasture = 0.100. Similar values to these ones have been derived in other

watersheds of Guatemala and other Central American countries (Abt, 2002).

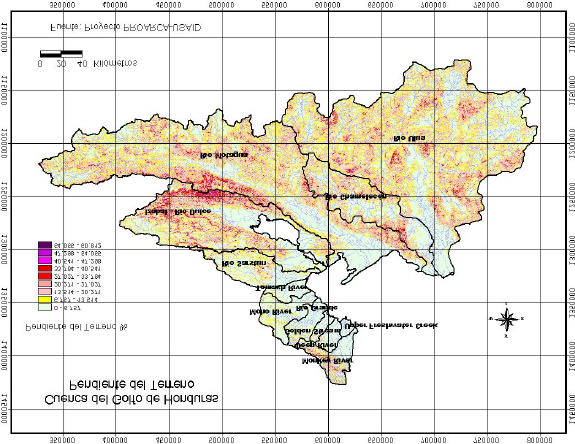

Figures 2.1-4 and 2.1-5 show the elevation and the slopes maps derived from the elevation map. Figure

2.1-6 presents a map with the annual distribution of rainfall within the Gulf of Honduras watershed. .The

results of the superposition of these maps are presented in the map shown by Figure 2.1-7 which depicts

the potential erosion for the watershed. In this map the potential erosion in shown from low to high with

ranges of grey and green colours for low erosion potential to reds and black for high erosion. These

ranges were arbitrarily selected in order to be to show relative differences among the watersheds.

However, the digital map is very useful for planning watershed management interventions in areas with

land use conflicts like for instance intensive agriculture in high slope areas.

2.1.3.2 Sediment Rates

No information was found on sediment measurements of the tributaries of the Gulf of Honduras. In order

to get a "ball-park" estimate of the sediment contribution for rivers the average river discharges were

multiplied by an average concentration of sediments. To illustrate this Table 2.1-4 shows the average

discharges of the main tributaries to the gulf (Table 2.1-4) and the corresponding load assuming an

average concentration of 500 mg/L (Abt 2002). Sediment measurements in other watersheds of

June 2, 2003

8

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Guatemala oscillate between 50 and 3000 mg/L with an average around 500 mg/L. In other watershed

concentrations between 100 y 400 mg/L have been found for dissolved solids INSIVUMEH (2002).

Table 2.1-4. Preliminary Estimation of the sediment Loasd of the main tributaries of the Gulf of Honduras

River Name

Country (ies)

Mean Discharge

Sediment Discharge**

(m3/sec)

(ton/día)

Stann Creek River

Belize

40

1728

Monkey River

Belize

63

2722

Rio Grande

Belize

26

1123

Moho River

Belize

37

1598

Sarstoon

Belize, Guatemala

160*

6912

Rio Dulce

Guatemala

300*

12960

Motagua

Guatemala

530*

22896

Ulua

Honduras

690*

29808

Chamelecon

Honduras

370 *

15984

Total

95731

* Heyman and Kjerfve, 1999

**Asumes an average concentartion of 500mg/L

June 2, 2003

9

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-3. Land Use Coverage Gulf of Honduras

June 2, 2003

10

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-4. Digital Elevation Map- Gulf of Honduras

June 2, 2003

11

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-5. Slope Map- Gulf of Honduras Watershed

June 2, 2003

12

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-6. Average Rainfall- Gulf of Honduras Watershed

June 2, 2003

13

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1 -7. Erosión Potential Index- Gulf of Honduras Watershed

June 2, 2003

14

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

2.1.4

Shoreline Classification

The shoreline of the region is highly variable, consisting of geologically-controlled structures to recent

sedimentary features. Belize's costal zone stretches approximately 375 kilometers, though only a portion

of this is in the Project Area. The geomorphology of this region is influenced by five parallel submarine

ridges of continental origin that trend NNE to SSW. These five ridges sit on a continental shelf that is

approximately 15 to 40 km wide, and which contains the 220 km long Belize Barrier Reef, extending

from the Mexican border in the north to Sapodilla Cays in the south. The southern half of the Belize

coast, the area within the Project Area, consists of sandy beach ridges and smaller coastal swamps. A

shelf lagoon exists along the southern part of the Belize coast, widening towards the south in effect

mirroring the width of the shelf. The coastal zone of the south is generally more diverse and richer than

that in the north. The Belize coast includes such diverse features as estuaries and lagoons, barrier beaches

with beach ridges and saline tidal swamps, cays, mangrove forests, seagrass beds, patch reefs, barrier

reefs and cays.

The Guatemalan coastline has a variety of habitats as well. Though lacking a barrier reef, the coast is

similarly diverse with vast mangrove areas (La Graciosa, Cocoli River, Santo Tomas, Punta Manabique,

Sarstoon-Temash), leading to river mouths and estuaries (Rio Dulce), the large Bahía de Amatique with

its vast shallow waters and sea grasses (Bahia Graciosas), the sandy Punta Manabique peninsula (an

accretionary feature built from riverine sediments from the east), and long beaches leading to the river

mouths of Motagua, San Francisco, and Piteros. These river mouths contain estuaries and various

important freshwater and coastal habitats.

The Honduran coastal area is marked by long beaches, vast mangroves, and offshore cays with corals and

mangroves. The major city on the coast, Puerto Cortés, has nearby beaches that are a tourist attraction.

The river mouths (primarily the Ulua) exhibit a rich vegetative growth, and contain important habitats.

The extensive coral reefs of Honduras are farther to the east of the Project Area.

2.1.5

Climate

2.1.5.1 Temperature

Temperatures in the study area tend to have small temporal variability due to the location of the Gulf in

the sub-tropical region. Temperatures are generally highest along the coast, with mean annual values of

approximately 28 degrees Centigrade. At higher altitudes, the temperature drops, such that the

temperature is about 20 degrees at altitudes of 500 to 1000 m. Much of the population lives at these

intermediate altitudes. The annual range of temperature is quite small.

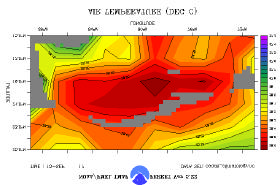

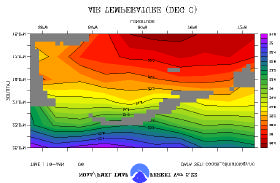

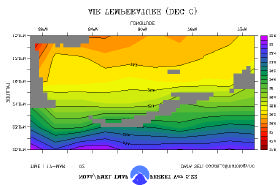

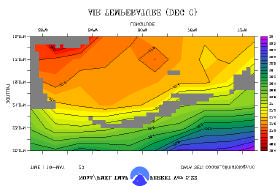

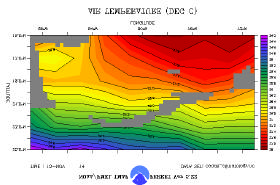

Figure 2.1-8 shows a regional view of mean monthly temperatures in the overall Caribbean Sea, as well

as in the Gulf of Honduras. Temperature fluctuations over the Gulf of Honduras are on the order of a

couple of degrees Centigrade.

June 2, 2003

15

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-8. Mean Monthly Temperatures for the Gulf of Honduras Marine Area

2.1.5.2 Precipitation

The climate of the Gulf of Honduras falls within the Rainy-Warm type, and presents two distinct climatic

periods. A rainy season lasts from June to October with the highest levels of rainfall and humidity,

reduction in wind speed, and higher temperatures. The dry season lasts from November to May, and is

characterized by a reduction in temperature and rainfall (Porting, 1976). These seasonal variations of

meteorological conditions in the area are caused by north-south migrations of the Intertropical

Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which is found near the equator in winter and at about 10°N at the end of

summer season.

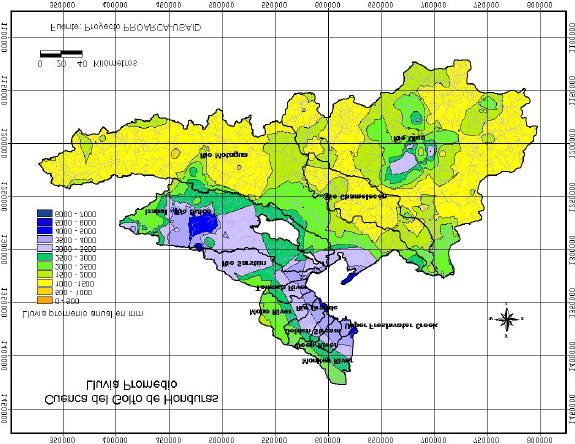

The yearly rainfall averages from 3,000 to 4,000 mm in the coastal regions of the western Cayman Sea

(Galleges, 1996; Heyman and Kjerfve, 2000) and up to 10,000 mm per year in the Maya Mountains. At

the same time, the offshore areas of the Gulf of Honduras get approximately 40% of the mainland rainfall.

June 2, 2003

16

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

This estimate is based on measurements at Carrie Bow Cay from 1976 through 1980 (Rützler and

Ferraris, 1982). Air temperatures in the Gulf vary seasonally from 23°C in winter to 28°C in summer

(Heyman and Kjerfve, 2000).

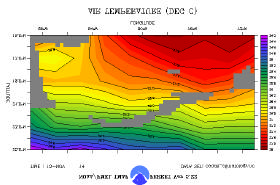

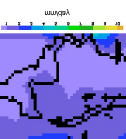

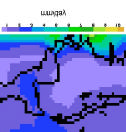

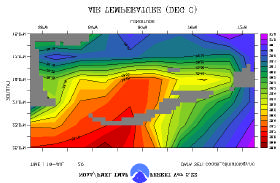

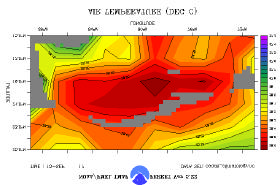

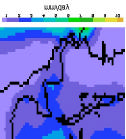

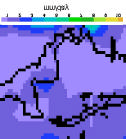

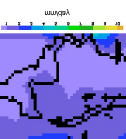

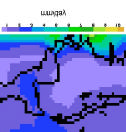

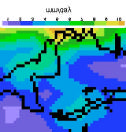

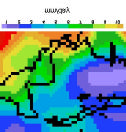

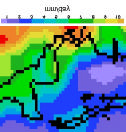

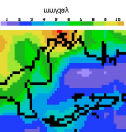

Rainfall is presented in Figures 2.1-9 and 2.1-10. Figure 2.1-9 shows the monthly patterns of

precipitation, with the higher values over the mountainous areas and lower values over the Gulf itself.

The rainy season patterns are clearly demonstrated. Figure 2.1-10 shows the monthly mean precipitation

over the Gulf of Honduras, ranging from a low of 50 mm per month in the dry season, to about 275

mm/month in the rainy season. The rainfall in the interior mountainous areas is much larger.

Figure 2.1-9. Regional Precipitation Patterns in the Gulf of Honduras

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Source (http://orbit35i.nesdis.noaa.gov/arad/gpcp/)

June 2, 2003

17

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.1-10. Mean Monthly Precipitation in the Gulf of Honduras

Precipitation in the Gulf of Honduras

300

250

200

150

mm/month 100

50

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

months

2.1.5.3 Winds

Winds are important to water quality in that they generate currents, thus affecting mixing and advection,

and create waves, which resuspend bottom sediments causing higher turbidity. Recent evidence

(WRIScS, 2001) indicates that resuspension is as influential as river flooding in generating turbid water in

the coastal zone of the Gulf.

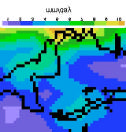

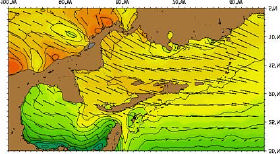

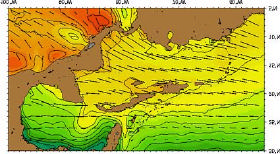

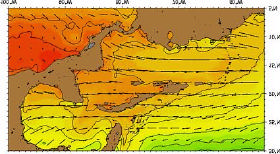

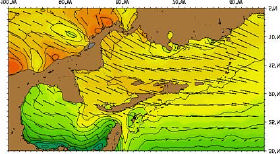

In the Gulf of Honduras, the wind pattern is dominated by northeasterly trade winds during the year

(Figure 2.1-11) with speeds ranging from 3 to 8 m/s. The winds in the Gulf are stronger during winter

months when the ITCZ shifts south. In summer, the southward component of the trade winds is minimal.

June 2, 2003

18

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

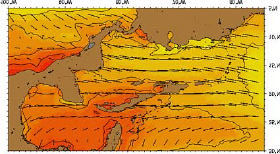

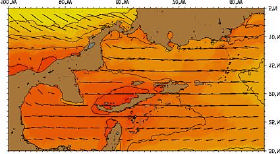

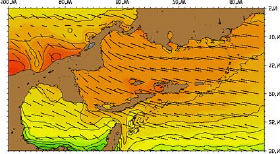

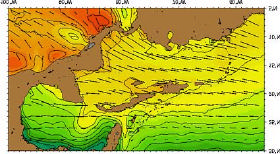

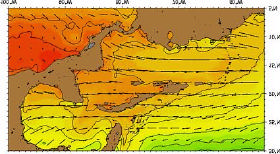

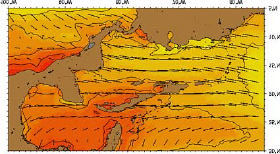

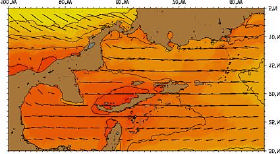

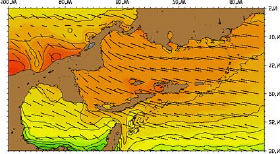

Figure 2.1-11. Seasonal Evolution of Sea Surface Temperatures (Pathfinder AVHRR) and Surface Winds

(NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis Project) for the Caribbean Sea.

January

March

May

July

September

November

Each month represents an eleven-year average from 1985 through 1995 (from Samuels, 2002).

Typical synoptic meteorological features that cause variations in speed and direction of trade winds and

other changes in meteorological conditions are `weekly' easterly waves, some of which develop into

tropical storms and hurricanes causing transient circulation, mixing, coastal upwelling and storm surge

(Mooers and Maul, 1998). During winter months, occasional cold-air outbreaks from the north (called

`northers') associated with the passage of the polar atmospheric front cause strong winds from the north

and drops in air temperature.

2.1.5.4 Hurricanes

Tropical storms and hurricanes regularly cross the Gulf of Honduras between August and October. The

frequency of tropical storms increases from south to north, being 20 storms per century of the area of the

Bahía de Amatique and up to 60 storms per century at the northeastern limit of the Gulf of Honduras

(Heyman and Kjerfve, 2000). A recent example of a hurricane that impinged upon the area of the Gulf

was category 5 Hurricane Mitch, which hit the region in October 1998 causing devastating effects on

June 2, 2003

19

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

coastal areas. For example, precipitation estimates for Mitch for the total storm event in Honduras and

Nicaragua have ranged from 1,200 to 1,800 mm for locations receiving the heaviest rainfall (National

Climatic Data Center, 1999).

The patterns of hurricanes reaching the Gulf of Honduras are indicated in Figure 2.1-12. Most hurricanes

trend east-to-west, however, some recurve and display complex tracks. East-to-west trending hurricanes

generate their largest winds in the southwest direction, towards the coasts.

Figure 2.1-12. Map of Hurricane Tracks in the Gulf of Honduras, 1921-1999

(See Appendix D)

2.2

Geology and Geomorphology

The geology of the Gulf of Honduras region is quite complex, being situated in an area of active tectonics

(illustrated by strong seismicity and active volcanism). The marine portion of the region reflects the

presence of active marine dynamics, including subduction and collision tectonics. The deep Caribbean

basin with its chain of islands is a reflection of these complex dynamics. The landward portion reflects

both modern processes of volcanism and alluvial processes, but also ancient metasediments.

2.2.1

Geology

The geology of Belize consists primarily of three types of formations. The northern, hilly Maya

Mountain region consists of metamorphosed sediments (metasediments) and granitic intrusions, whereas

the southern area consists of alluvial material. The metasediments are the oldest rocks in Belize, dating to

the Paleozoic era at 300 million years old. These are part of the Santa Rosa Group, comprised of fine-

grained phyllites, sla tes, and mudstones. The coastal plain sediments are young, dating to the tertiary

period at about 10 million years. These sediments are thought to be of riverine, not marine, origin.

Primary soil types are Ossory (derived from metasediments), Stopper (derived from granitic rocks),

Melinda (derived from alluviual material), Puletan (also from alluvium), and tintal soils (wet, swampy

type soils).

The geology of Guatemala is more complex, consisting of four primary physiographic units: coastal

plain, Izabal Depression, sedimentary highlands, and Motagua depression. Soils are mixed, and include

the Inca, Chocon, Chacalate, Alluvial, and Manabique soil types. UNEP (1995) provides a brief

description of these soils. The coastal plain consists primarily of alluvial material from the Quaternary

era. The sedimentary highlands are comprised of carbonates of the Mico Mountains, well-known for its

karst topography. The Motagua depression is floored by Quaternary era alluvium as well, and includes

the Punta de Manabique, a large, sandy barrier.

The geology of Honduras within our study area consists primarily of the following units. The coastal

areas consist mainly of Quaternary and Cretaceous rocks, primarily consisting of alluvium and intrusive

units. The lithology of the alluvium unit is mainly surficial bounders, cobbles, gravel, sand, and mud

while the intrusive unit consists of granite, granodiorite and diorite. The origin of the alluvium is

sedimentary while the intrusive rocks are plutonic in orig in. The environment of deposition for the

alluvium is continental marine.

June 2, 2003

20

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Intermediate (or farther south) from the coastal plain is a Paleozoic unit called Cacaguapa Shist, a

metamorphic rock with an unknown environment of deposition. This unit consists of rocks such as schist,

phyllite, gneiss, quartzite, marble and quartz veins.

The mountainous areas to the south are Tertiary and Cretaceous in age and are from the Matagalpa, Patre

Miguel, and Yojoa formations. These rocks are pyroclastic, volcanoclastic (tuff), and sedimentary mixed

rock types, respectively. The environment of deposition for the Matagalpa and Padre Miguel formations

is continental and the Yojoa is marine in origin.

The primary soil types in the Honduras coastal areas are beach sands, alluvial sediments, marshes and

bogs and various silty loam soils.

2.2.2

Coastal Processes and Coastal Erosion

The Gulf of Honduras has quite a mixed range of coastal processes occurring within it. Along the Belize

sector of the Gulf, the shoreline is characterized by a vast barrier reef of more than 200 km in extent,

which protects the shoreline from open Caribbean wave action. Waves are generally locally generated

within the lagoon. The numerous small rivers along the Belize coast provide some sediment to the

shoreline, but not an excessive amount. In general, the littoral transport is from north to south, though the

magnitude of this transport has not been estimated. Numerous types of shorelines exist (see section

2.1.4), some of which are sandy beaches, but many of which are mangroves, swamps, etc. This north-to-

south littoral drift is primarily wave-driven, but parallels the general southward residual drift of the

coastal currents.

Within Guatemala, the littoral transport is varied. Along with the western side of the Bahía de Amatique,

the littoral transport is to the south, and sediments from the rivers there nourish the attractive beaches to

the south. Due to the protection afforded by the northern reefs and the bay itself, littoral transport is

somewhat slow. In the central and eastern portions of the Bahía de Amatique, open Caribbean waves

cannot propagate. This central protected area is characterized instead by locally generated waves, and

relative stability of the coast and sea floor. Hurricanes are the dominant destabilizing force in this region,

and rivers bring continual sediments to the coastal areas. Along the northeast portion of the Guatemalan

coast, from the Honduras border to the tip of the Punta de Manabique, the littoral transport is on average

from west to east, though transport at any given time may be in either direction depending on the wind

conditions. This section of shoreline is exposed to open Caribbean waves, and likely has the largest

waves of the Guatemalan coast. Fortunately, the rivers of Guatemala and Honduras provide a sufficient

sediment supply, so coastal accretion dominates over erosion, as evidenced by the growth of Punta de

Manabique over historical time periods (despite some localized episodes of erosion).

Along the Honduran coast, the general littoral transport is from west to east also, as the open Caribbean

waves approach the shoreline mainly from east to west. The rivers of Honduras tend to nourish the coast,

although coastal indentations (at Puerto Cortés, for example) may create local areas of erosion. In

general, the beaches of Honduras appear to be relatively stable and sandy.

2.3

Oceanography

This section describes oceanographic conditions in the Gulf of Honduras and adjacent Caribbean Sea. The

introduction sub-section gives a brief background on the oceanography of the western Caribbean Sea.

The focus of sub-sections 2.3.1 and 2.3. is on the space-time variability of basic properties of seawater,

June 2, 2003

21

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

such as temperature, salinity, transparency, and water chemistry, as well as on the circulation patterns that

cause variations in seawater characteristics.

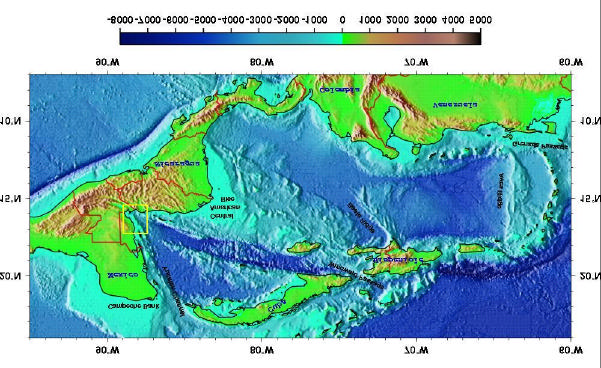

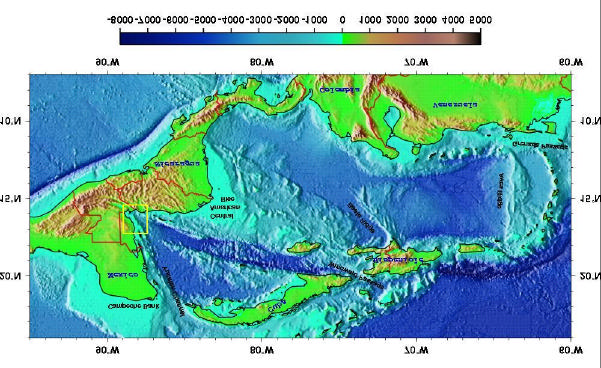

The topography of the Caribbean Sea (Figure 2.3-1) shows a succession of five deep basins separated by

sills of less than 2000 m depth and set apart from the main Atlantic basins by a chain of islands. Several

passages that connect the sea with the Atlantic Ocean have sill depths of 740 -2200 m. The sea has more

than one connection with the main ocean basins. The northern basin is connected with the Gulf of

Mexico through the Yucatan Strait.

On average, evaporation exceeds precipitation throughout the Caribbean Sea (Etter et al., 1987). The

excess of evaporation over precipitation is not balanced by freshwater inputs from rivers on a basin wide

scale, which makes this American Mediterranean Sea a concentration basin. The annual mean salinity,

averaged over the upper 200 meters, increases from 36.09 at the inflow through the Lesser Antilles to

36.19 in the Yucatan Strait (Etter et al., 1987). These surface salinities are relatively low due to the

influence of Amazon and Orinoco River water, however. Therefore, the density increase associated with

the concentration process is insufficient to overcome strong density stratification and cause deep vertical

convection. As a result, deep-water renewal occurs due to sporadic inflow of oceanic water from outside

(Wust, 1964).

The Amazon River and Orinoco River waters are advected to the northwest with the Caribbean Current.

On average, 15 -20% of the surface water that enters the Caribbean Sea is derived from the brackish

waters of the Orinoco and Amazon River estuaries (Moore et al., 1986). The influence of river runoff is

strongly seasonal, with strongest flow occurring between May and November, that is, during the wet

season.

Freshwater inputs from local rivers play a significant role in modifying stratification and formation of

buoyancy driven circulation patterns on regional space scales (Murray and Young, 1985). Therefore, the

Caribbean Sea is highly stratified in the upper 1200 m of the water column; weakly stratified between

1200 and 2000 m; and nearly homogeneous below 2000 m. This water structure is directly related to the

sill depths of the Antilles Islands arc, which impede the flow of deep water into the Caribbean (Gordon,

1967).

Water masses entering the Caribbean originate in both the North Atlantic and the South Atlantic oceans.

Several water masses can be distinguished in the Cayman basin (Wust 1964; Gordon 1967; Sukhovey,

1980; Gallegos, 1996). The surface water mass occupies the upper 50 m of the water column. It has

salinity around 36.0 in winter and 35.8 in summer. Below the surface water lies the subsurface layer

(Subtropical UnderWater (SUW)) occupying a depth from about 50 to 250 m. The core of this water

mass is located at about 100-m depth. It forms the salinity maximum, with salinity around 36.5 and

temperature in the range of 21 to 23°C. The next 500 m layer of the water column is dominated by

Western North Atlantic Central Water (WNACW) with a typical temperature range of 20 8°C and

salinity range of 36.3 - 35.2. Deeper, at about 700 m, the characteristic salinity minimum of Antarctic

Intermediate Water (AAIW), salinity near 34.9 and temperature near 7°C, can be traced through the

Caribbean Sea. The deep waters are remarkably uniform, with temperature of about 4°C and salinity of

about 35.

The main circulation feature of the Caribbean Sea (Figure 2.3-1) is the Caribbean Current (Wust, 1964;

Gordon, 1967; Kinder, 1983; Kinder et al., 1985), the throughflow carrying waters from the Atlantic

Ocean into the Gulf of Mexico with a mean transport (Gallegos, 1996) of about 30 Sv (1 Sv = 106m3/s).

In the western Caribbean, the mean velocity of the Caribbean Current is about 0.5 m/s (Fratantoni, 2001).

June 2, 2003

22

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Its intensity has a strong seasonal cycle (Gallegos, 1996) with higher current velocities during spring-

summer time (about 0.8 m/s) and slower currents during autumn-winter months (about 0.4 m/s).

June 2, 2003

23

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.3-1. The Caribbean Basin: Bathymetry and Circulation

The circulation in the Caribbean experiences much variation in both space and time, some of it in the

form of mesoscale eddies and meanders of the Caribbean Current (Mooers and Maul, 1998; Andrade and

Barton, 2000). The major mechanisms that may cause generation of the mesoscale eddies in the western

Caribbean are interaction of the Caribbean Current with bottom topography (Molinari et al., 1981), wind

forcing, and shear instability of the flow. Quasi-permanent cyclonic eddies are formed between the

Caribbean Current and the coast in the Colombian and Cayman basins. High-resolution numerical

models (Navy Layered Ocean Model, for instance) reveal that an anti-clockwise rotating (cyclonic) eddy

is a quasi-permanent circulation feature in the western Cayman Sea

(http://www7320.nrlssc.navy.mil/global_nlom/globalnlom/ias.html). It determines flow variability in the

deep part of the Gulf of Honduras. Coastal circulation is driven by wind and buoyancy fluxes formed by

river runoff and rainfall (Murray and Young, 1985).

The Gulf of Honduras is part of the Cayman basin of the western Caribbean Sea (Figure 2.3-1). This

water body has an area of about 10,000 km2. It includes Bahía de Amatique, the entire Caribbean coast of

Guatemala, the eastern part of the coast of Honduras, and the southern part of the Belize Barrier Reef

Lagoon. The western part of the gulf, about 60 km off shore, is rather shallow (0 30 m). Several coral

reefs, which form the southern portion of the MesoAmerican Barrier Reef System (MBRS), are located at

the northwest border of the Gulf. Large freshwater inputs from the Motagua, Sarstoon and Dulce Rivers

limit reef development in the central part of the Gulf to a few isolated corals and small patch reefs, such

as Hunting Cay, for instance. The northeastern part of the Gulf includes a portion of the deep Cayman

Trench. The continental slope is rather steep and the water depth drops abruptly from about 30 m at the

shelf break to 2000 m depth in the northeast. Therefore, one can expect that both coastal and open ocean

processes may play a role in driving circulation dynamics and determine variability of seawater properties

in the Gulf of Honduras.

June 2, 2003

24

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

2.3.1

Seawater Properties in the Gulf of Honduras

2.3.1.1 Seawater Temperature

Water temperature is an important parameter for a tropical coastal ecosystem because reef corals are

sensitive even to subtle changes in water temperature. The temperatures at which they grow best are

between 25°C and 29°C. Increase in water temperature eventually causes coral bleaching and decay

(Kramer and Kramer, 2000). In spite of that, data on the variability of water temperature in the Gulf are

scarce and fragmentary. While seasonal variability is well documented on a basin scale on the basis of

satellite data, little is known about regional peculiarities of space-time distribution of seawater properties

in the Gulf.

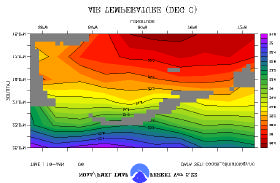

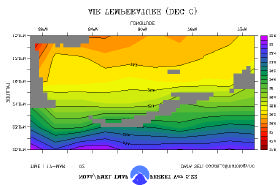

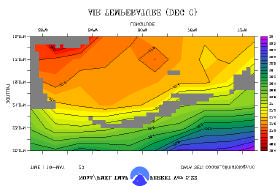

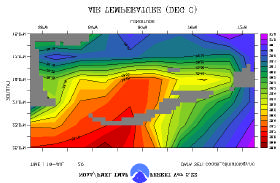

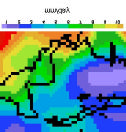

Long-term averages of remotely-sensed sea-surface temperatures (SST) for the Caribbean Sea (Figure

2.3-2) reveal little changes within the seasonal cycle. According to these data SST in the Gulf of

Honduras varies within a range from 27°C (January February) to 29°C (August September). Brenes

et al. (2001) studied time variations of sea-surface temperature at a specific location (Cayos Cochinos) in

the area adjacent to the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Honduras using high-resolution data from NOAA

- 12 and NOAA - 14 polar orbiting satellites. Sea surface temperature data were also obtained in situ to

ground truth remote observations.

The data showed a well-defined seasonal cycle (Figure 2.3-2), in which low temperatures observed during

the first months of the year were mainly associated with coastal upwelling that occurred in response to

seasonal intensification of the trade winds on a local scale. At the same time, the open sea area showed a

similar decrease in temperature due to intensification of open sea upwelling within the cyclonic mesoscale

eddy (sub-section 2.3.3). Summer temperatures were approximately 1°C higher than could be expected

from mean climatological data.

Figure 2.3-2. Surface (left) and Bottom (right) Water Temperature Variations at Cayos Cochinos in 1993

1996.

Source: Koltes et al., 2002

Seawater properties in the coastal zone of the western part of the Gulf were measured in February 1999

(PROARCA COSTAS, 2003) in the region of the Snake Cays (Port Honduras area). The data showed

that sea surface temperature varied during the period of the survey in the range from 29 to 32°C, which is

about 2°C higher than could be expected from mean climatological estimates. In 2001, a typical

thickness of the upper mixed layer (UML), which has vertically uniform temperature and salinity, was

about 15 m in the northwest portion of the Gulf (WRIScS, 2001). The temperature showed a vertical

distribution with coolest waters at depth offshore and warmest waters at the surface and inshore. The

June 2, 2003

25

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

temperature range was from 28.5 to 31°C. A thermocline developed in the offshore areas at depths of 15

20 m. It is possible that the thermocline did not exist in shallower areas due to wave -induced mixing.

2.3.1.2 Seawater Salinity

The open sea surface salinity in the western Caribbean Sea is rather uniform with values around 36.2

(Sukhovey, 1980; Gallegos, 1996). The coastal water salinities may vary over a wide range from 5 to 35

(Figure 2.3-3), with lowest salinities observed close to major rivers. On average, offshore salinities are

almost constant throughout the dry season (until June), then drop dramatically in July August, and

gradually increase in September November (CZMAI, 1999).

Throughout the year, the lowest salinities in the Gulf are found in the Bahía de Amatique, a shallow

estuarine basin. It is a body of semi-enclosed coastal waters with a connection to the sea and in which

salinity is considerably diluted due to the influence of freshwater discharged from land. In this shallow

water body, with an average depth of less than 10m, salinity fluctuates throughout the year from 10

(during wet season) to 30 (during dry season). During the rainy season, there is a clear gradient with

salinities from almost zero salinity at the mouths of the Sarstoon, Laguna Izabel, and Motagua rivers to 16

in the outermost part of the bay (Yañez-Arancibia, 1994; Salaverría and Rosales, 1993). There is also

vertical stratification of salinity, with average bottom salinity values of 33.7. Higher bottom salinities

occur due to the estuarine-type circulation, with a shoreward flow of open seawater near the bottom,

creating a `salt wedge', and a seaward flow in the surface layer (Figure 2.3-4). The circulation is formed

due to the existence of a density gradient, which forces freshwater to move offshore and overlay more

saline (denser) open seawater.

Observations during 2001 in the northwestern portion of the Gulf revealed salinity values from 33.5 to

34.8, with readings increasing with depth and decreasing shoreward (WRIScS, 2001). The range of

salinity variations in this area was thus much less than the range of salinity variability in the survey area

at Snake Cays (Figure 2.3-3). Other observations (WRIScS, 2001) indicate that salinity even along the

inner reef margins can fall to about 32 during periods of intense river flooding.

June 2, 2003

26

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.3-3. Surface Salinity Distribution in the Snake Cays (Western Gulf)

June 2, 2003

27

Abt Associates Inc. / Woods Hole Group

Preliminary TDA

Figure 2.3-4. Schematic Representation of Salinity Distribution and Flows in a Typical Estuarine System

Source: Tomczak, 1996

2.3.1.3 Water Transparency

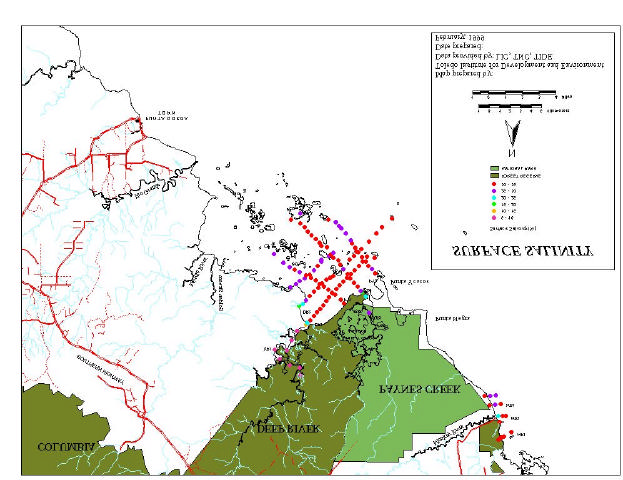

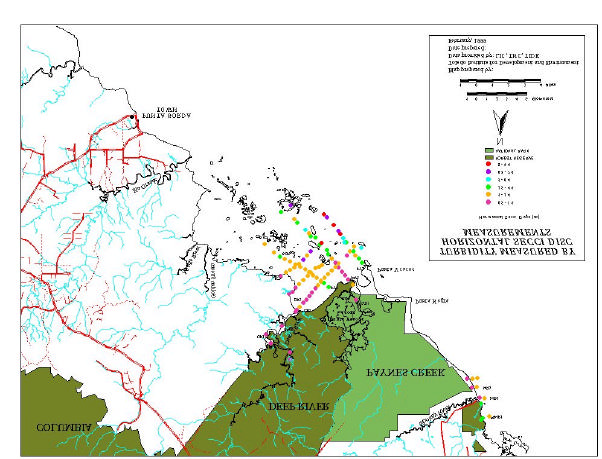

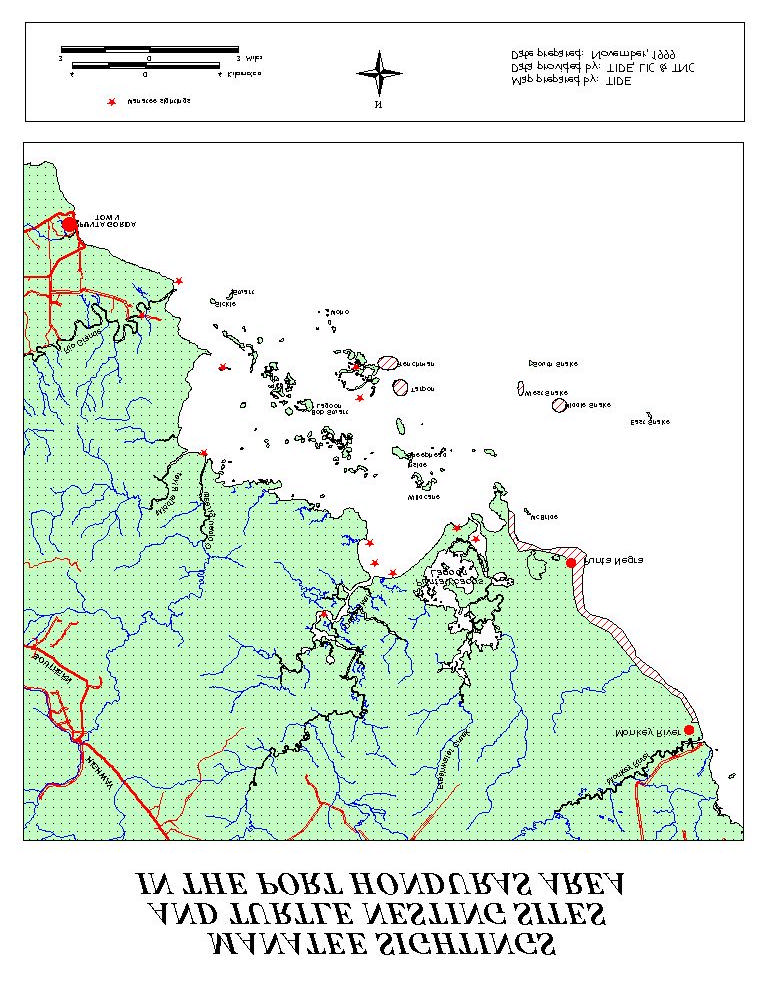

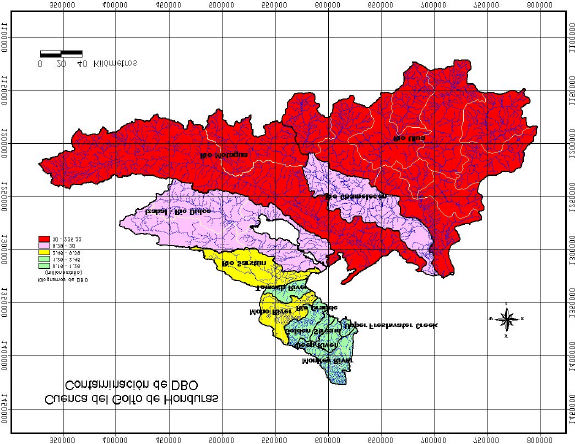

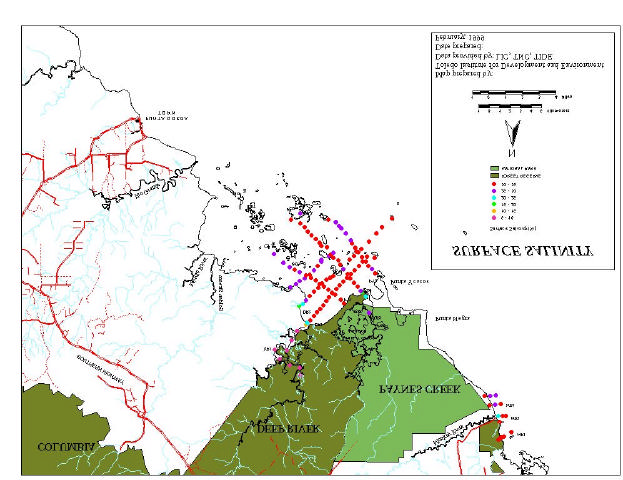

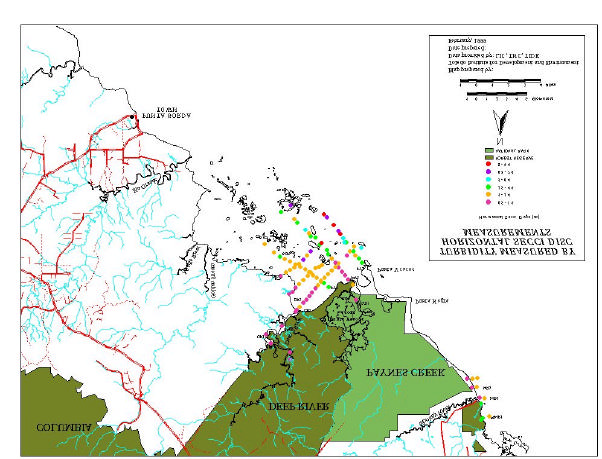

Water transparency is a critical parameter for a tropical marine system, because coral reefs need low